Some Stories Don't Make the Stage, But They Are More Than Worthy

How to Still Honor A Story like Rubiela from Soacha, Colombia?

The taxi dropped me outside a low-slung series of apartments in Soacha, an industrial city an hour outside of Bogota. Cumbia and Vallenato blared over dogs barking. Rubiela, a sweet women in her fifties with crimson hair pulled back in a ponytail, opened the door and announced she was making lunch for us. I’ve learned to never refuse food or drink when welcomed into someone’s home, but I told her I wasn’t expecting a full meal. She looked straight at me and said, “What, you’re just going to stare at me the whole time while I eat?” We both burst into laughter.

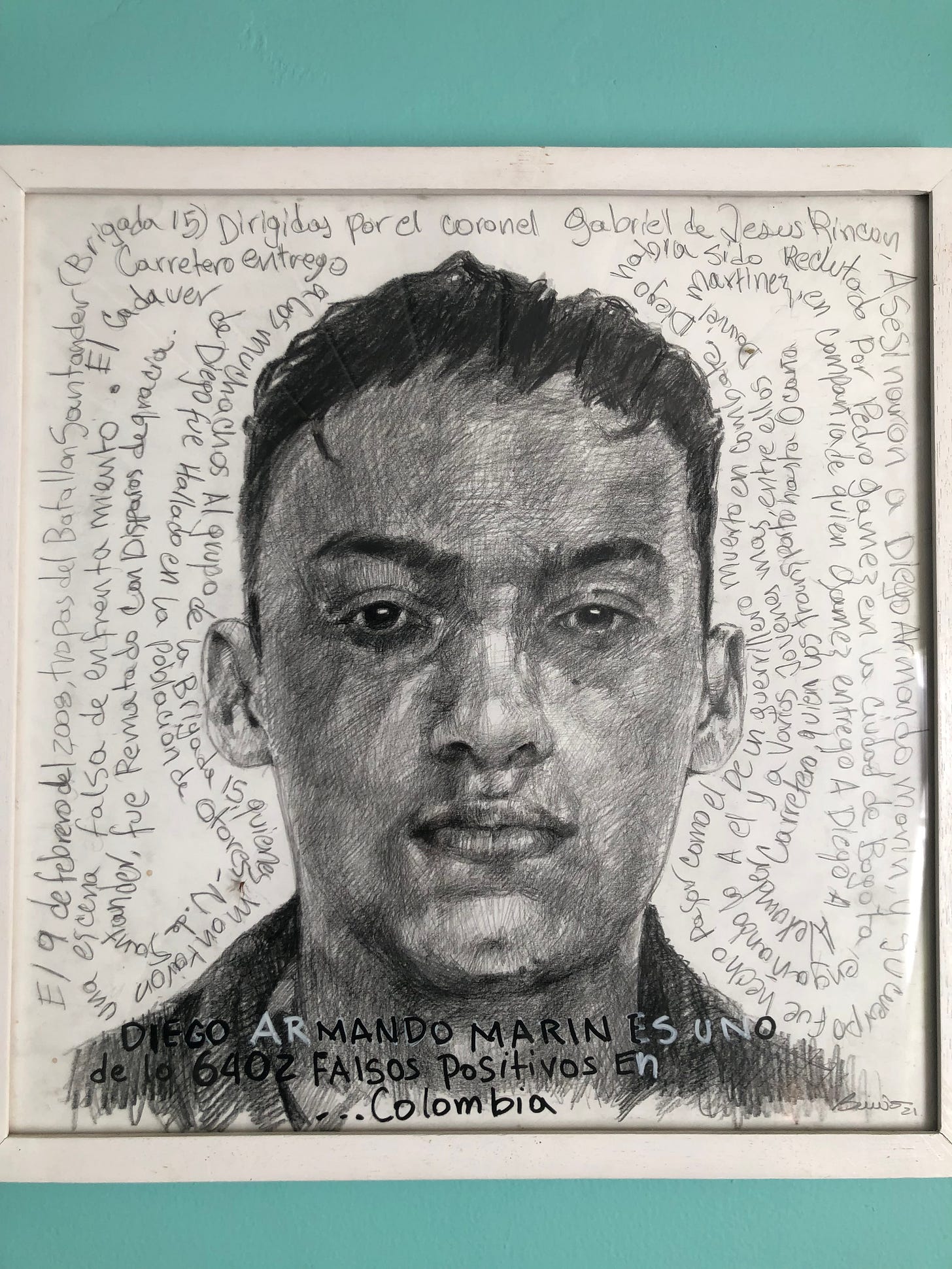

Rubiela is one of the leaders of MAFAPO, a group of women whose sons or brothers were victims in Colombia’s False Positive scandal. From 2002-2008, over 6,400 young men from mostly poor, rural backgrounds were lured by job recruiters, taken across the country, dressed in FARC military fatigues, and then killed by the military. It was an attempt by Alvaro Uribe’s government to bolster numbers of enemy kills to show the government was winning the war against the FARC insurgency. It was in these years that the U.S. was routinely giving Colombia over $600 million annually, most of it for military hardware and training, as part of Plan Colombia.

I had gone to Colombia because I was interested in the national process of reconciliation the country has undergone in the wake of its fifty-year civil conflict. The landmark 2016 peace accord between the government and the FARC included a Special Justice Tribunal (known as the JEP) to oversee the thousands of cases of extrajudicial murder, torture, and disappearances. It also included a comprehensive, years-long Reconciliation Commission in which victimizers publicly apologized to the relatives of the victims, and gave details about the fateful day. This, according to experts, gives relatives’ of victims some consolation, though full reconciliation is often elusive.

I talked to many Colombians about the conflict when I was there, and everyone has friends and/or relatives who were deeply affected, often in terrible ways. And while the wounds may be raw, there is so much less rancor and resentment than one might imagine. I attended parties where there were former leaders of different factions who only a decade ago were mortal enemies. (That said, while violence is much less than it was, it is far from peaceful. I wrote about this in greater detail in my March 2023 piece Letter from Medellin.)

In the U.S. we haven’t had a civil war (since 1865) and we can barely talk to each other. We segregate politically, living and working in different parts of the country. We have entirely different sources of news and information, distinct vocabularies to talk about politics and culture, and live openly disdainful of each other. The play I was working on when I visited Colombia in November 2022 has shifted away from reconciliation though. Now titled TAKES ALL KINDS, it is about our country’s fissures, our crisis of democracy, and the people who are moving the country forward in some of the most stuck and polarized places.

I had hoped to write a play that brought some of the stories and lessons of Colombia’s post-conflict reconciliation to stand in relief against America’s fractures. I realized that the context was too different. And that in our country, at least right now, there is little interest in reconciliation. We are entrenched in our opposing camps, and we are still fighting. Given the stakes of the coming election, perhaps this is understandable.

Yet I often think of the stories I heard in Colombia and marvel at the way people found joy and grace In their everyday lives despite horrific recent histories. In doing the work of journalistic theater, audiences often ask how people feel about having their story portrayed onstage. What I’ve found over and over again is that the people who share their stories with me do so because they want to have their stories shared more widely. To be listened to at length is something most people don’t have in their lives. To have their story then shared widely, and received deeply by strangers, is something even fewer of us experience. (I wrote about this in greater detail in last month’s essay.)

The biggest turmoil I feel is when I’m not able to include someone’s story in my show. There are always stories and people that are profound and moving or funny and unforgettable that I’m not able to include in my theater pieces. Rubiela is an inspiring woman, and her story has stayed with me. Maybe I can go back to Colombia and deepen my research towards a whole new show.

Until then, I wanted to include some of her story as told to me, edited and translated. It is not the same as the embodied version people are used to seeing in my shows. (I think there’s value in seeing the difference.) This is an oral history of an afternoon. Though it doesn’t include the time after our interview and lunch when we walked the neighborhood and stopped at a local chicha spot and had a whole different set of conversations—the journalism of hanging out always expands in unpredictable ways.

It starts with her welcoming me at the door. She spoke while making us lunch: steaks, eggs, vegetables, salad, and fresh squeezed juice. I marvelled at her ability to cook such a complicated meal, with three burners going and half a dozen pots and pans, while recounting her ordeal. And she told the story with unwavering kindness and grace.

Rubiela:

“Hi Daniel, come in, come in. I'm making lunch for us. Of course I am. What you're going to stare at me the whole time while I eat? And my nephew is coming. All my children are abroad in Spain. And I live here alone.

I'm a widow. Twenty-six years ago. My husband was everything. We met when we were kids, Daniel. He was a farmer, my family were farmers. He lived on one side of the mountain, and I lived on the other. Near Tolima. It was hard losing him, Daniel. So I live alone, with God and the Virgin here.

My parents were illiterate, but they were saints. Honest, honorable people. We are seven siblings, five boys and two girls. (Lighting the stove) I always wanted my children to get ahead, to have a good job. I had four children, all boys.My family is beautiful Daniel. I am proud of my family.

Well, when they took my son away from me, they took him out of here on the second floor. He was twenty years old. He had served his military service as a policeman, but he didn't like it at all. He said, I'm going to find a job to help me. Because it was always me and the four guys.

It was Tuesday February 5, 2008. I went to the factory at four in the morning to work making clothes. When I came home in the afternoon, my other son said to me, "Did you hear that Diego hasn't come home? He went out this morning and was with a boy and we don't know who the boy was. And we haven’t seen Diego since.”

So the next day passed. And then Thursday. Diego didn't call me. Sometimes when he had nothing to do he would go to his Aunt’s house and then in the afternoon he’d come home to sleep and eat. Or sometimes he’d go to the countryside to see his grandparents. To help them harvest bananas or to cut grass, the same way I did growing up.

But nothing. Friday passed. He hadn't called me. So I said I'm going to the prosecutor's office, to get them to start doing something (“poner las pillas” put in their batteries). And then my sister said, “Diego called me, I talked to him.” And what a relief. But he told my sister, "Auntie, I'm so far away." And my sister said she felt a sadness in his voice.

I kept looking, I would go from six in the morning to six in the evening or six in the evening to six in the morning to look for him, Daniel. I went to the prosecutor's office, filed a complaint, but they didn't receive it. More time passed. I was just crying. And I never said anything at my work. I ate all that pain by myself. It's not for nothing, but everyone in the company loved me. I got on well with everybody. Especially with the boys, because I had four boys, right? And still searching and searching for Diego, but nothing.

In September, a man from the police passed by and said that there were a lot of boys there in Ocaña, and bodies were appearing. He said they would take them, put them in bags, make a hole and put up to seven people in a hole.

They called me on the first of October at four o'clock in the afternoon. I came home and they said Diego’s gone. Oh my god, you can't imagine the pain, Daniel. That was terrible, Daniel. He doesn't know life. He was only twenty years old. Your heart hurts so much. But I never lost faith in God. I've always told God. When he takes somebody, don't take me like that. I know we're all going to die, Daniel. But don’t ever take my child like that. Someone else comes along, takes your child, disposes of their lives? No. For that I can’t forgive him. Nobody has the right to dispose of a life. The only one who should dispose of life is God. No one else.

So I arrived, Daniel. To identify the body.

(To her nephew) In one minute I’ll serve you, my love. I’m just making a salad.

They had taken off the boys clothes. Put khaki clothes on, to make them seem like guerrillas. He was killed on February 9. The body had been decomposed. The face was not his (was not recognizable).

And I went to hearings. For every boy there were ten people who killed him. Rincon-Amado, the Colonel, I thought he was a lawyer at first. Well dressed and all. Paolino Coronado. There were about fourteen of us (mothers). We almost didn't go to the JEP because they had the man who killed our boys in one room, and we were in another room. So we only saw them on the TV screen. That's why I almost didn't go.

What I liked the most were the projects we did together. I parachuted with an army lieutenant who was involved in the False Positives scandal, but not with my son. It was a very nice process. He's a tall guy, when I met him it was like I saw my son, because my son was also tall. They took us to the Truth Commission. We hugged. He called me one day. He said I want to have a process with you. They made us paint a vase. And after we had painted the vase, we broke it. Oh! I was crying because it was breaking my heart. And I buried myself in the ground up to my neck in a cemetery in the Centro de La Memoria with some of the other mothers.

At least now it is known that the government was the one that did that. Now God is giving me inner peace. It’s not for a person to forgive. It is only God who forgives. What am I to say, that I forgive? Ay, no.

My heart is clean. You have to live well, not get sick with hatred, with rage, with rancor, and drag the family down. No. My family is beautiful. Very much in love with God. I want us to live with clean hearts, Daniel. And that's how I live.

.

Beautiful as always, Dan. When I fulfilled a lifelong dream of going to Vietnam in 2002 (fighting the Vietnam war was one of the most fulfilling experiences of my life), I expected a lot of hostility to me as an American. But, at least outwardly, I experienced none. Just the opposite. Numerous young men would follow me around wanting to hear all about The United States and to practice their English (as opposed to the French their parents and grandparents knew).